How inclined would you be to watch a 77 minute documentary on weaving in an indigenous Indian community? The answer is probably not much. You’re probably content with the jumper you bought in H&M last week and cannot envision yourself ever having to use a loom, post-apocalyptic scenario aside. But, if this form has taught us anything it’s that no subject is too small so long as there is a passion behind it, and so long as that passion invigorates the material, with the hope that it then invigorates its audience.”

After a much felt absence from filmmaking (no less than 15 years in fact), director Pat Murphy returns to Irish screens with a piece that is, by some accounts, unquantifiable. Yes, Tana Bana doesn’t look specifically at the craft as much as examine the community and the culture that exists around it. But it’s also true that Tana Bana is meandering in focus, moving in and out of the lives of the weavers, designers and sellers that make up the process in an arbitrary fashion. It’s refreshing to see a film that has freed itself from the obligation to relay simple, bite-sized facts. Here, Murphy is more intrigued by the people, their voices and the effervescent timbre of the place; storytelling takes a back seat as the mood and atmosphere of this Indian locus push to the fore. We become engrossed by the rhythms of this world. Images of a loom spinning mechanically or a piece of fabric being submerged in dye are simple but manage to entrance.

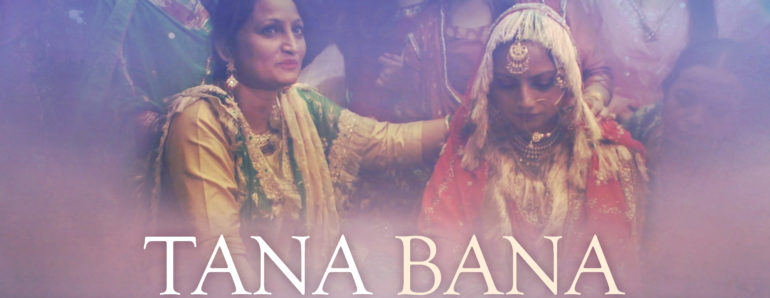

For all this visual beauty, what Tana Bana really captures is how these strenuous rituals, archaic though they may seem to first-world viewers, reinforce the culture and identity of these people, as if bound to it, as if (with the certainty of sounding pretentious) woven into the very fabric of their lives. In some regard, it seems as if Murphy’s veritable allegiances lie with the women in this story. A reiterated note about the obligation to wear burqas appears at various points. At others, we see the intricate design of resplendent sarees decorating a recent bride. She picks at an interesting notion here, as if to state that the marginalised role of women in this community is shaped and perpetuated by the industry it is built upon. Females are either to be covered up or ornately costumed according to their religion, objectified in either case. But such a moment of precise probing seems out of touch with an otherwise free-flowing, wandering scope. It’s the only weak note in an otherwise engaging, insightful and undeniably colourful film.