Pier Paolo Pasolini lived an infamous life, made many infamous films and died an infamous death. Of course, you’d expect no less from a gay Marxist who adapted both the New Testament and the Marquis de Sade for the big screen. As a biopic of a filmmaker, Pasolini achieves two great coups: it doesn’t shy away from the scandals that its subject actively pursued, and it ably mirrors his style and filmmaking eccentricities. Whether that manifests into a cohesive whole is debatable, but the late Italian’s influence looms in every frame.”

If anyone had to direct a film about the life (or death) of Pier Paolo Pasolini, few would seem as well qualified as Abel Ferrara. They would appear to be kindred spirits; though their moral viewpoints might have differed, both are concerned with the point at which flesh, violence and faith intersect. Indeed, Pasolini fits very neatly into Ferrara’s filmography, sitting well alongside the chilly elegance of the likes of King Of New York or The Addiction and the portrait of moral corruption offered by recent fare like Welcome To New York. If it isn’t quite up to those film’s standards, it’s not for lack of trying. Pasolini is nothing if not ambitious.

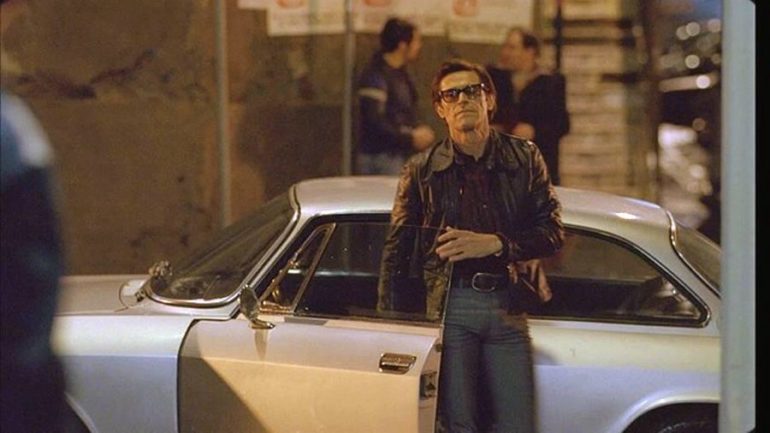

The film opens with Pasolini (Willem Dafoe) giving an interview to French journalists whilst they all watch a French dub of the newly-finished Saló. They ask him what his title is; director, screenwriter, dialogist. Pasolini responds that he is simply a writer. This interview is lifted almost wholesale from his last recorded interview (Watch it here), and there’s a sense of fatalism to his bearing, both in reality and in this film, as if he knows his time is running out. Pasolini shares this pessimism, but not to an extent that it becomes overly dour. Pasolini himself was not so; Willem Dafoe may seem like stunt casting given his physical resemblance to Pasolini, but he magnificently inhabits a man defined by a quiet sense of mischief. The role calls for intelligence, a sense of humour and a certain world-weariness, and Dafoe balances all these demands in a terrific interpretation. Dafoe’s distinct American twang is but one of many languages and accents that clash here, but such consistency isn’t the hallmark of Pasolini’s films, so it’s unlikely he’d have minded.

Though primarily set around the last day of Pasolini’s life (2nd November 1975), there are flashbacks to formative moments (political influences and youthful sexual dalliances) to fill in gaps as Ferrara attempts to link the man’s past to the politics of his present. Even more daring are attempts to dramatize scenes from Pasolini’s unproduced screenplay Porno-Teo-Kolossal, which is as confrontational and offbeat as one would expect. DoP Stefano Falivene paints pitch-black nights and muted sunshined days, shot with a crispness that few of Pasolini’s films enjoyed. Indeed, the surface sheen could be accused of dulling Pasolini‘s edge a little. His films felt truly anarchic, a luxury which Pasolini affords itself only to a point.

Maurizio Braucci’s screenplay offers a believable account of the man’s last day, channelling Pasolini’s way of writing and shooting into a film that can feel haphazard in the way it’s told. As with the languages, we’re constantly swapping between plotlines and ideas as the man himself might have done. Pasolini is best appreciated by fans of its subject’s work. Newcomers might also get a good idea of what he’s about, but its admirable refusal to cleave to a true story template means it might alienate. In short, it sells Pasolini to a tee. Cinema’s greatest scandaliser would have expected no less.