Upon its initial release, Gillian Flynn’s crime novel Gone Girl guaranteed discussion. Is it a piece of nonsensical pulp, or a cutting satire of many a sacred cow? Is it misogynistic or empowering? Is protagonist Nick Dunne an idiot or a scapegoat? Or an antagonist? Whatever the stance, it’s a marketer’s wet dream. The film will not provide answers. If nothing else, David Fincher’s film of Flynn’s adaptation of the novel (At which point does the author give way to the auteur? Layers upon layers, like marriage itself.) is the best advertisement for pre-nuptial agreements since Anna-Nicole Smith said ‘I do’.

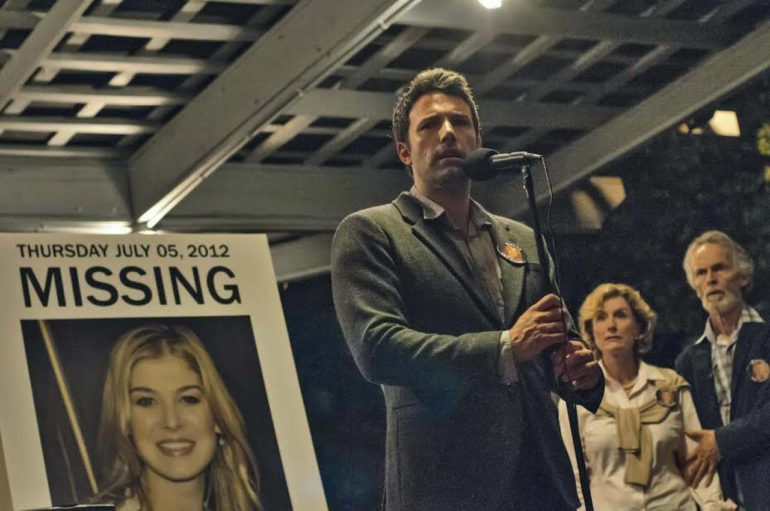

As Nick Dunne (Ben Affleck, all soft-in-the-middle American charm) reflects on his five years of marriage, so David Fincher reflects on his filmography to date. He’s a distinctive director, but Gone Girl may be his biggest reach for auteur status yet. He’s adapting another public transport stalwart after The Girl With The Dragon Tattoo, one that combines the twists of The Game with the breakneck pacing of Fight Club and the monied, elegant aesthetic of The Social Network. Still, we’re not navel-gazing here. Fincher’s dealing with some spiky material, and the resulting film is shorn of respite or pity, either for its characters or its audience. Much like the central figure of Amy Elliot Dunne (Rosamund Pike), Gone Girl is a dangerous, enigmatic tease.

If there is a reason that Gone Girl doesn’t reach the heights of Se7en or Zodiac, it’s that the film is much like the life Nick and Amy appear to have built for themselves. It might have a bit too much polish on the surface, but that’s at least part of the point. Smart, wealthy trust-funded New Yorkers relocate to leafy Missouri? It’s all too perfect.

On the morning of their fifth wedding anniversary, Amy disappears from their home after an apparent struggle? It’s all too perfect.

After initial investigations, all police and media attention begins to turn on quiet academic Nick? It’s beyond perfect.

The marriage looks less like a genuine union than a series of picture postcards, like those people you see in picture frames in shops, grinning as if their lives depended on it. On the surface, Fincher’s film boasts a similar artifice. Jeff Cronenweth’s cinematography is a less sepia-tinged varietal of his work on The Social Network. Flynn’s dialogue is ripe with sarcasm and delicious bon-mots. There’s an elegant superficiality to proceedings that belies something much more sinister underneath. Nothing new here; Soderbergh gave us a similarly handsome potboiler with last year’s Side Effects. What makes Gone Girl stand out is the bitterness and bite at the heart of it all. Media, manipulation, marriage: all are under Fincher’s dissecting gaze.

The first act narrative flips back and forth between the days after Amy’s disappearance and the courtship & early days of her and Nick’s marriage. Initial cutesy flirtations are drowned out by Trent Reznor and Atticus Ross’ score, which coolly recalls Howard Shore’s works for Cronenberg and Badalamenti’s score for Twin Peaks. Right from the start, mystery surrounds them like the sugar dust that surrounds the pair to frame their first kiss. It scarcely matters what they say, because as Gone Girl goes on, the less and less we feel we can trust anything the pair say, least of all to each other.

Then again, how can Amy have any say when she’s disappeared? As hotshot defence lawyer Tanner Bolt (Tyler Perry, smooth) informs Nick, the police have no hope of a conviction without a body. She’s gone, but is she dead? Either way, Rosamund Pike brings her to life. Initially alluring, Amy proves an enigma wrapped in velour wrapped in a brittle shield of self-importance. A talented writer and successful New York columnist (before financial pressures and family illness forced her and Nick back to Nick’s home town), Amy turns her skills to beautifully verbose diary entries. Pike has the beauty and wit of a girl-next-door, but also the intellectual poise and coolness to keep the other characters and the audience guessing. She doesn’t seem to hate her husband so much as the whole world; she harbours resentment of her parents for the series of children’s books based on her life. Saying she has chemistry with Affleck is moot; after all, this is doomed to end badly. Rather, let us say they make able sparring partners, with Affleck switching nimbly between collected and exasperated as the evidence against him mounts.

Flynn’s novel could be accused of being simple pulpy noir, and the film has its fair share of salty dialogue and bloodshed. However, there are many critical potshots taken in the book that the film is keen to uphold. There’s a certain class element and an urban-rural divide at work that feeds into the paranoia of the piece. Two New York writers breezing into rural Missouri are doomed to stick out (Her parents, a pair of boo-hiss stuck-ups, are even more conspicuous). Even local boy Nick seems a world away from his twin sister Margo, who comes to be his most loyal supporter as the case builds. As Margo, The Leftovers actress Carrie Coon delivers the film’s best performance. Warm and earthy, she takes no prisoners (“Whoever took her’s bound to bring her back.”). It’s a great role for Coon; she’s one of the few characters who isn’t constantly lying through her teeth. One of the joys of this script is the fact that it has no room for red herrings; every side character and moment feels important. As Detective Boney (Kim Dickens) and Officer Gilpin (Patrick Fugit) sort through the evidence, characters like Amy’s ex Desi (Neil Patrick Harris) or Nick’s student Andie (Emily Ratajkowski) appear early on, only to bring down the house of cards when they resurface later. Trust no-one.

Throughout Gone Girl, the only presence more keenly felt than Amy’s is that of the media. Reporters of all methods and makes (Sela Ward’s professional precision, Missy Pyle’s shrieking tabloid) burst in, cameras flashing. The media’s role in Gone Girl flits between judge, jury and salvation. As a former J-Lo accessory, Affleck knows what it’s like to feel intimidated by every press call and clamour. His casting is but one sly stroke in what may be Fincher’s funniest film. Whether it’s the sharp wits on display or the oft-preposterousness of the plot machinations, Gone Girl is rife with black humour. It’s needed when the plot continues to wrong-foot the viewer up to the final reel, with an ending of such simultaneous possibility and hopelessness that it will doubtlessly leave some people exasperated. Flynn has altered her ending, albeit not to an extent that her fans will feel alienated. Thanks to David Fincher, Gone Girl will provoke reactions of all shades all over again.