For a significant portion of the 1980s, Peter Greenaway enjoyed the reputation of enfant terrible of British cinema. His second feature, The Draughtsman’s Contract (1982) announced his singular vision and unique style (theatrical, painterly and precise), and set him apart as a filmmaker of rare talent and ability. Greenaway cemented this reputation with a run of films, including A Zed and Two Noughts (1985), The Belly of an Architect (1987) and Drowning by Numbers (1988), before hitting his critical and commercial peak with The Cook, The Thief, His Wife and Her Lover in 1989. But as his singularity of vision turned into self-indulgence, audiences soon tired of his stubborn persistence in rehashing the same themes again and again. Greenaway’s acolytes may have dwindled in the 25 years since his creative peak, but he hasn’t given up yet.

Set in the year 1590, Goltzius and the Pelican Company is the story of Dutch print-maker Hendrick Goltzius (Ramsey Nasr) and his quest to promote the New Humanism writings of Ovid. Alongside the other members of his publishing company, Goltzius travels from The Hague to Alsace to seek funding for an expensive printing press from the wealthy Margrave (F. Murray Abraham). Being a bit of a dirty old man, the Margrave persuades Goltzius to illustrate and print a personalised edition of Old Testament stories demonstrating the six sexual taboos instead. In return for the Margrave’s sponsorship, he agrees to stage six dramatizations of these erotic tales, performed by his company, for the pleasure of the Margrave and his court.

Greenaway continues to insist on using the theatre (and by extension, the cinema) as form of licensed voyeurism. The endless depictions of incest, adultery, paedophilia, prostitution and necrophilia soon become wearing, and moral outrage has never felt so boring. The lurid sex scenes are about as titillating as the weigh-in segments of Operation Transformation. In spite of his best efforts to shock, by far the most insidious and disturbing aspect of Greenaway’s film is its overt racism. A group of non-speaking extras are rendered in blackface to portray the Margrave’s slaves. He comments that their complexion gives them the ability to disappear into the background, therefore making them the perfect servants. I assume that this is supposed to be a joke. It’s not funny. And it doesn’t end there – two characters talk about “growing black babies like tobacco plants in Virginia”, and the racial epithets directed at Ebola (played by Martinican Lisette Malidor) demonstrate an insidious bigotry which is more shocking than any scenes of full-frontal nudity, sodomy or rape.

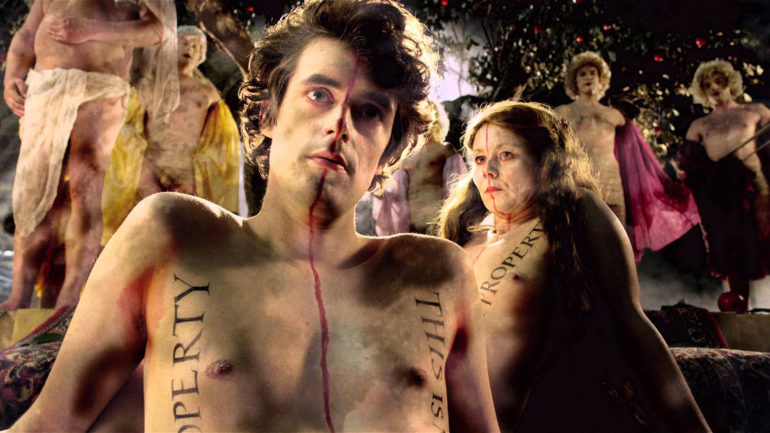

When it comes to visual framing or theatrical long shots, nobody does it better than Greenaway. But each beautifully-framed sequence is buried under layers of handwritten text projected onto the bodies of the actors, shimmering water filters or superimposed with erotic animations. This constant over-egging is exhausting. Goltzius and the Pelican Company feels like sitting through a two-hour Enya video with added buggery. It’s like Jessica Simpson or Justin Bieber – pretty but hollower than a Russian nesting doll and deeply unpleasant to be around. Greenaway has ploughed the same furrow for the past twenty years. His audience has disappeared and he has nothing new to offer, yet he keeps going. I can’t help but think of Grady Tripp, the failed novelist played by Michael Douglas in Curtis Hanson’s Wonder Boys. When asked why he continues to write long after he has forgotten what it was that he was writing about, he simply answers, “I couldn’t stop.”