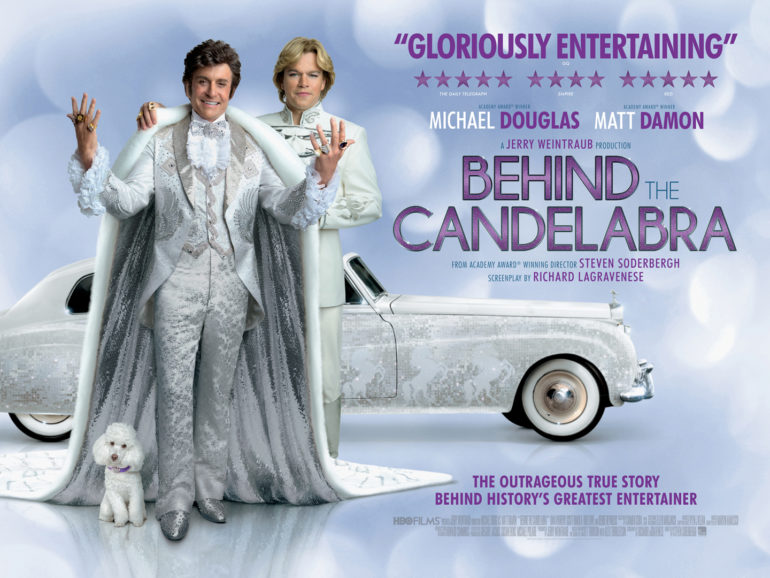

If you’ve ever watched footage of a Liberace concert, you’d be astonished how anyone couldn’t guess he was gay. Yet, his affectations and the excesses of his lifestyle endeared him to a largely older audience who saw (or at least chose to see) a nice guy who hadn’t yet met the right girl. Early on in Behind The Candelabra, Bob Black (Scott Bakula) and his friend/date Scott Thorson (Matt Damon) go to see Liberace (Michael Douglas) perform in Las Vegas. As he surveys the dazzling stage, Thorson declares Liberace’s act to be ‘the gayest thing he’s ever seen’. Black nods at the greying crowd sat in front of them and notes, “They don’t have any idea that he’s gay.” For a performer to be gay in the late 1970s would have been career suicide, so Liberace cannily hid it in plain sight.”

Much as Liberace covered up his homosexuality publicly with bling, Steven Soderbergh’s Behind The Candelabra does much the same thing. It’s obviously a biopic, but there’s more than enough glitter and glass to make you forget that fact. Based on Thorson’s memoirs of his six-year relationship with Liberace, it sticks to some well-worn tropes but also manages to shed a different light on someone most people might have thought they had figured out. Behind that candelabrum and under the jewel-encrusted furs lay a man driven by a need to distance himself from an impoverished past. It sounds like literature, but then Jay Gatsby never had surgically-enhanced, drug-addicted male lovers.

Michael Douglas’ take on Liberace walks a fine line between the lonely and the creepy. Liberace hires Thorson, and sets him up with a house and fancy cars. However, he then attempts to reconstruct Thorson’s face to make them look alike, and initiates proceedings to adopt him. Despite this plainly odd behaviour, Douglas blends enough of the showman in Liberace into his private self to create a portrait that is both selfish and seductive. Damon enters Liberace’s life with wide-eyed wonder and attempts to escape under a cloud and a Botoxed frown. Both are incredibly magnetic. Meanwhile, the glazed-over stare of Rob Lowe steals every scene he’s in as perma-high plastic surgeon Dr. Startz. He’s the standout in a supporting cast that is given relatively little to work with (Dan Akroyd as Liberace’s manager Seymour Heller suffers particularly in that regard).

Despite a theatrical release on this side of the pond, Behind The Candelabra was made for TV by HBO. This is because, as Soderbergh puts it, the story was ‘too gay’ for any big studio. Screenwriter Richard LaGravanese doesn’t shy away from what might be construed as ‘too gay’ for the mainstream. Liberace was camp as Christmas, and so is the film. The cinematography and costumes are full of light and sparkle as to be effervescent. This dazzle, along with Douglas’ grin, help overcome some of the darker elements of the story. LaGravanese and Soderbergh do take a few liberties; Damon is much older than Thorson was when he began his relationship with Liberace. Being ‘too gay’ is one thing, but Liberace’s behaviour would be hideously errant in any kind of relationship.

However, as frank as it may be, Behind The Candelabra isn’t a plunge into the influence of aberrance, like John Maybury’s Bacon bio Love Is The Devil. Truth be told, the most shocking thing is how such an extraordinary life can still fit a biopic template. There are the initial highs, the midpoint conflicts, the third act lows and attempts at redemption towards the end. Soderbergh’s films often feel like his own unique take on an established genre, but this biopic is perhaps the one film on his CV where his influence is felt the least. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing; it just means the story takes precedence over any Soderbergh subversions. It’s a made-for-TV true story, but one with terrific performances and dazzling opulence worthy of W?adziu Valentino Liberace himself.