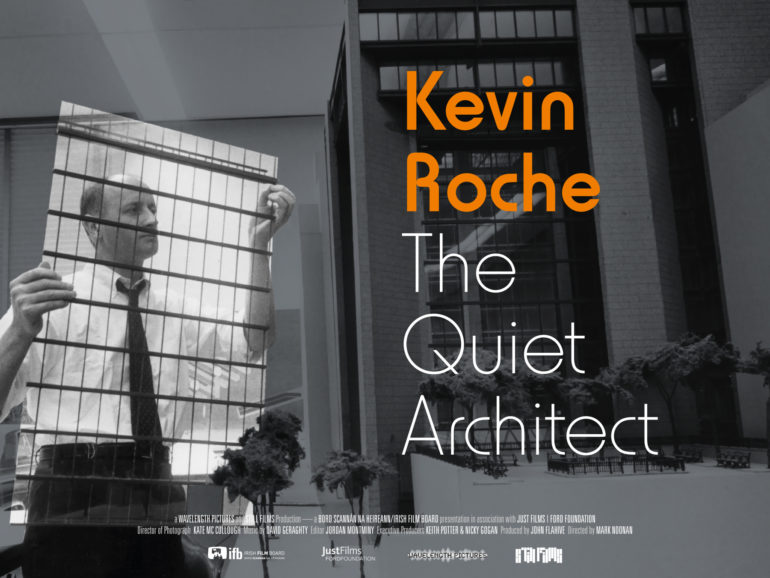

Out today at the Irish Film Institute is Mark Noonan’s new documentary Kevin Roche: The Quiet Architect. Scannain caught up with the director ahead of the film’s release.

The film, directed by Irish filmmaker and UCD architecture graduate Mark Noonan, delves into the life and work of award-winning Irish-American architect, Kevin Roche, showcasing his remarkable architectural achievements on the big screen.

Still working at age 95, Pritzker Prize winning Irish-American architect Kevin Roche is an enigma. He’s reached the top of his profession, but has little interest in celebrity and eschews the label “Starchitect”. Despite a lifetime of acclaimed work that includes 40 years designing new galleries for The Met in New York, he has no intention of ever retiring. He graduated from UCD in 1945, and after more than 60 years in the USA, his first Irish project, the Convention Centre Dublin, opened in 2010. Roche’s architectural philosophy focuses on creating “a community for a modern society” and he has been credited with creating green buildings before they became part of the public consciousness.

He has won awards for his designs of over 300 major buildings around the world, among them the Pritzker Prize in 1982 – the highest honour given to a living architect. Some of his best known work includes the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York which he has worked on for almost 50 years, the revolutionary Oakland Museum of California, the Ford Foundation and United Nations Plaza in Manhattan, A Centre For the Arts at the Wesleyan University, corporate campuses for Bouygues in Paris and Banco Santander in Madrid. Roche has also been the subject of special exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art, the Architectural Association of Ireland in Dublin, and the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. Kevin lives and works in Hamden, Connecticut.

Kevin Roche: The Quiet Architect was produced by John Flahive for Wavelength Pictures in association with Still Films, with the participation of the Irish Film Board / Bord Scannáin na hÉireann, and Just Films|Ford Foundation.

The film premiered as the closing film of the recent IFI Documentary Film Festival. “It’s my first time to make a documentary first of all, so it was my first time to have something play at the IFI Documentary Film Festival. I saw a few films during the festival, which was a really wonderful festival. It was a big honour to close it. And I was a bit surprised by how we sold out the screening so quickly. The film is a niche film, quite a specialised subject matter. I was really delighted. Especially given how much the IFI means to me. I’ve been going there since I was 18, so half my life basically. It was very special to premiere a movie at the IFI. I’m really grateful for their support and for the support of the film there as well. And now it will be released there from Friday.”

Financing a film like this can be tricky. “It was a convoluted thing. It was quite a long process, as it is with documentaries I’m learning. It all started off with the producer [John Flahive] seeing an article about Kevin Roche and then remembering that I was an architect, which I think was my only qualification. We’d met in Berlin years ago and he’d learned that I was an architect. So he contacted me about that and then we made an application for development to the Irish Film Board. They gave us a small bit of money to develop it, so that we could fly to America and shoot some scenes and see what we had. We did that in 2014 and then from that we had a 4 minute promo and we approached the Ford Foundation with the promo. We told them that we’d love to make a film about this guy who designed their headquarters and who has this really great philosophy on life and architecture and on humanity. And they loved it. Loved the promo, loved the idea, and came on board as the majority funder. They gave more than 50% of the budget and were extremely supportive. There were no strings attached, they trusted our instincts and told us to come back when we were done and they’d help us with a US release. With them in and with the Film Board wanting to support us we then got a few other small funders, like the Graham Foundation who give grants to works of fiction and works of film. We approached them and the Connecticut Architecture Foundation. Pieces of money from Ireland and America made up the rest, as well as Section 481 for the last bit. Thankfully I was out of that as it was with the producers. Nicky Gogan of Still Films came onboard as soon as the budget starting going up and we realised that we might be eligible for the tax credit. We wanted a great creative Irish-based producer. I was in Block T at the time writing in an office there and Nicky was next door to me and I loved her work so I introduced her to John Flahive. It was a perfect fit. Nicky has built a great company and they have a great love of slightly left-field documentaries. The kind of things that you don’t see every day. She loved the theme of architecture and our approach, and she loved working with our crew, with Kate McCullough, and David Geraghty, and our editor Jordan Montminy. She like the team that we had and is proud of the movie.”

Kate McCullough’s style as cinematographer seems to perfectly match the architecture of Kevin Roche. “I would gave Kate a huge amount of credit. We talked about an overall visual aesthetic, but then of course his buidlings are so different that you do have to treat each building as a separate scene. Some are better viewed from above, others from the ground with elegant tracking shots, others are viewed better in tilt-shift or composed very static shots. Kate has a very playful visual sensibility. She with every project she brings that. Like with something like The Farthest. You can see her visual sensibility in that. It’s just gorgeous. So wonderfully shot and you can see certain preoccupations visually that occur again and again in her work, which is really beautiful to see. She loves shooting upwards and playing with diagonals and giving a very dynamic energy to it.She was very excited to be working on it at the time. She was refurbishing her house so she was working with an architect and they were designing something. I think there was a nice symmetry of her talking to these architects, going out and filming the buildings, and then going home and discussing with her architect about her own domestic situation. It was a funny little series of events while we were filming.”

Noonan’s last film was the small Irish drama You’re Ugly Too, which was his feature debut as director. The Quiet Architect is his first documentary film so there was a transition to overcome. “It was quite exciting. It is a bit scary as with documentary you don’t have the script. We’d a vague outline and we knew what we were going to shoot but it was a puzzle. You have all the pieces but you are not quite sure how they are going to fit together. So the edit is much more exciting in one way and daunting in another. I did enjoy it, but there’s something about the scripted drama that reassures me. With a script you are on sure-footing. With documentaries the uncertainty can be challenging. You don’t really know if you have a film until quite late, usually in the edit. You always suspect that you have a film but it’s only really discovered in the edit. You exercise a different muscle with documentary. You’re putting it together in hindsight, reacting to the footage. In scripted drama you do that a little bit but you have the overall picture in your head for a long time. Documentary is a lot more organic. Exciting but very very challenging.”

Now 94 years of age The Quiet Architect is the first time that a feature documentary has been made about Kevin Roche. “He was very open and accommodating. He had done plenty of interviews and had short stuff made about him before. But he was quite bemused by this Irish crew who was flying over and back. Whenever we got another piece of the budget we booked tickets and flew over for a couple of weeks to film. Then we’d spent all that money and we’d be waiting another 3 to 4 months for another bit of money to come through, and we’d fly back to Connecticut or Minneapolis or to California. He was quite happy that we were filming a lot of the buildings that hadn’t gotten the recognition. That we were giving attention to these forgotten, not widely known buildings. He was pleased that we were shining a light on those. It’s funny, his only comment when we sent him the cut was “Far, far, far too long. You can take half an hour out of that easily”. I think he felt that there was far too much of him in it. He was being ultra self-deprecating.”

It wasn’t until the Convention Centre Dublin was commissioned in 1998 that he got to design a building in Ireland. “It’s sad, but also quite nice that he got to make a building here.He so easily might not have had that opportunity. It was a little bit of a mixed blessing in the end. It’s not the building or project that he had initially designed. And it took so much longer than he thought it would. It definitely made him hesitate about building here again. He did make the point that it was a lot easier to build on Wall St or in Manhattan than in Dublin. Which is kind of crazy given how intense and the level of bureaucracy involved in building in New York.”

Despite the “Starchitect” label Roche remains hugely humble to this day despite having created some iconic buildings. “He doesn’t see it that way. I asked him about walking around New York and seeing his buildings and they do dominate the skyline. He doesn’t think of them that way. They’re like children to him that have grown up and moved on. He keeps looking at the ground rather than up at all of the buildings that he has made. He is the antithesis of most superstar architects. He doesn’t consider himself American or Irish. He’s quite zen, a citizen of the world. In someways that is really quite Irish, to not take yourself too seriously and not get carried away. He’s been so flexible with his approach that maybe that’s why he hasn’t stood out as much as some of the more rigid Bauhaus architects like Walter Gropius or Mies van der Rohe (under whom he studied in Chicago). Kevin was more willing to build for the end-use or to mould the building to suit its surroundings. Whereas the fashionable and common thing was this very sleek and cold modernism that doesn’t really react with its environment. Function was not the priority compared to the form. If it leaked or not they didn’t really care. Kevin was more concerned with the end user.”

Kevin Roche: The Quiet Architect is out now. Tickets can be bought via the IFI website.