*This interview contains some minor spoilers for Queen and Country.*

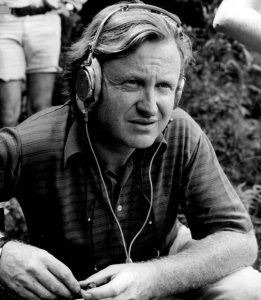

John Boorman is reflecting on reflecting. “You know, memory operates in a funny way. I was reading about memory recently, which said that if you relate a memory, you impose a layer on top of that memory. Each time you tell it, another layer is added.” This weekend sees him bringing more of his memories to the cinema screen, adding another layer to his eclectic, but always interesting CV. We meet him in the gilded lounge of Dublin’s Intercontinental Hotel to talk about the past, and how to bring it into the present.

Queen and Country is the long-awaited follow-up to his 1987 hit Hope and Glory. Based on Boorman’s own memories, we go from the 9-year-old Billy Rowan experiencing the Blitz to 18-year-old Billy (played in the film by Callum Turner) being conscripted. Why has Boorman chosen to revisit his cinematic alter ego now? “I always had it in mind to do it, but other things intervene. Also, when I started to think about it again, that period seemed somehow more historically interesting than it was right at the time, because it was a period when everything was changing. After the war, Britain was broke, and within a few years the greatest empire in the history of the world was gone completely.”

He continues optimistically, “At the same time, when the Labour government came in after the war, they did two very significant things. One was the National Health Service, and the other was the establishment of Secondary modern schools. For the first time, every child learned something about art and music, and that produced the kids that became the Rolling Stones and the Beatles, and the arts scene of the ‘60s.” Boorman found himself caught between the old and the new. “I remembered this generational gap,” he explains, “and how ‘we, the young’ could see that everything was going to be different now, whereas the older generation of soldiers were hanging on to the imperial Britain. So I thought it was suddenly more worth doing this tale than earlier, because of the distance.”

Despite all this change, Boorman recognizes its failure to completely take root. “It’s extraordinary that, sixty years ago, the coronation took place and she’s still on the throne. I mean, we all felt that that would all be swept away. The class system has been modified, ameliorated certainly, but it exists still supported by the notion of royalty and aristocracy. She’s a very nice lady, but what she stands for is, I think, so old-fashioned.”

Queen and Country is based closely (sometimes surprisingly so) on Boorman’s army experience. In adapting such a personal story for the screen, how does one draw the line between fact and fiction? “It’s very difficult to say exactly. Once you cast it, you’re changing things. It’s a bit of a mystery, the relationship between imagination and memory, because if you tell me the story of something that happened to you on the way here this morning, you’re already applying imagination to an event, and so that obviously has an effect.” As we go on, Boorman exercises his own memory, but we stick with Queen and Country for the moment.

“But what I can say is that all the characters in Queen and Country are based on actual people, and all the events took place, like the story of my first cigarette (It was smuggled in a jar of jam, before being dried and smoked), and the stealing of the clock.” The theft of a prize clock from the sergeant’s mess is one of the main plotlines in the film. “I’ll give you an example of how the needs of a film alter things: the Percy character (played by Caleb Landry Jones) actually stole more than one thing. He stole something every two weeks, and got it out of the camp by posting it. He did it four times and each time it brought the camp to a standstill. It was a deliberate policy of obstruction and terrorism, really, but I whittled it down to one incident; there wouldn’t be room to do the whole thing.”

Boorman was determined to do justice to his memories, even though certain elements were changed from Hope and Glory “When I was casting Sinéad Cusack to read the part of the mother (replacing Sarah Miles in the original film), she asked if I wanted her to impersonate the character from Hope and Glory. I said I’m not concerned about appearances; I’m concerned about the characters. What I did, when I was writing and shooting it, I asked myself the question: is it true? And that really was my guiding principle; did it ring true? Did it seem right to what really happened?”

That last question might be harder for Boorman to answer as the years go on. “The only regret I have is, with Hope and Glory, it’s based on my memories as a child of the Blitz, and I can no longer remember the memories; I can only remember the film!” He laughs at this point, but his voice suddenly gains a hint of melancholy “And I suspect the same will happen with Queen and Country.”

Despite his pursuit of truth, circumstance prevents Boorman and most any director from shooting in the exact locations where events take place. “We shot for three days on the Thames, at Shepperton where I lived. That’s where we moved to after our house was destroyed in the war. We shot the rest in Romania, because it was the only way we could afford to make the film. We built all the sets there, the army camp, the interiors of the house on the Thames, the street with the ‘50s shop exteriors. When you make a period film, everything has to be made or borrowed. Clothes, props, light switches, everything was different.”

This approach, of building everything from scratch, is a hangover of the making of Hope and Glory. “When I was trying to make Hope and Glory, it seemed like a small film. When I said we needed to build the whole street, one of the biggest sets ever built in England actually, they couldn’t believe this ‘small’ film would cost so much.” Still, the demands of the script and the setting must be met. “When you’re working in period,” Boorman explains, “it’s always expensive. A lot of the time, you can go to a costume house and get all the costumes for that period, but it’s more things like furniture, props, all the detail. Tony Pratt, who designed the film and whom I’ve worked with a lot over the years, is meticulous, even to the cables running down the side of a door. It has to be the cable that you would have at that time!”

In the film, Billy is court-martialed after he (unwittingly or otherwise) persuades a recruit to leave the army. Boorman did the same thing, and is keen to explain himself. “First of all, you have to say in any conflict that only about one in ten soldiers is in the front line. I think we went into the army very reluctantly. We couldn’t see the point of the Cold War or the Korean War; it seemed a futile exercise. When I had the job of lecturing soldiers who were going to go to Korea, I read up about it and it was clearly a war that shouldn’t have happened, based on a series of misunderstandings. So, this boy was the son of a left-wing Labour MP named Ian Mikardo, and he decided he didn’t want to go to Korea after listening to my lectures. MI5 came down and I was investigated.” The paranoia was inescapable, explains Boorman. “Everyone was afraid of Communism back then; they wanted to establish if I was a Communist sympathizer. The slogan at the time was ‘There’s a Red under every bed.’ So I was clearly subversive, but I did my best to conceal it, and I hid behind facts, and the facts made it pretty clear that it was an immoral war.”

The film deals with the fallout of Billy’s (and Boorman’s) actions, but the director ensures it’s not heavy-handed. “There’s nothing overtly ideological or political in the film, but it’s right under the surface all the way through. All the class differences between Billy and Ophelia (played by Tamsin Egerton) which make their relationship impossible at the time, and the attitudes towards royalty and empire, were all lying in there. It’s very representative, I think, of how people felt at that time.”

So, Boorman hasn’t softened his views in the intervening years. “No, not at all,” he declares emphatically. “George Bernard Shaw said two things. He said ‘if they pass a law that only men over 40 could go into battle, wars would soon come to an end,’ because it’s children who fight wars, 18-year-olds. He also said, ‘If a man is not a socialist when he’s young, he has no heart. If he’s not a Tory when by the time he’s 40, he has no sense!’ I was a rabid socialist when I was young, and I’ve always held those views, and I’m a passionate opponent of consumer capitalism.”

All this being said, his affection for the period and the people is what drives the film, rather than any regret or bitterness. “Any bitterness I felt at the time has been washed away by…” Boorman descends into a coy laugh before he can finish the sentence, leaving a pleasant air of mystery. “I certainly had a feeling of affection for that time and those events. And my family, of course. My sister’s return from Canada was volcanic.” Billy’s sister Dawn (Vanessa Kirby) makes the same homeward trek, bringing colour and a certain amount of disruption to their riverside home. “The extraordinary thing was that she stayed, and she did have an affair with the Percy character. That didn’t last very long, but her son was about 19 when she met his friend, who was 20, and she married him, a man 15 years her junior, and they were happily married for 30 years. When she died, he was absolutely distraught and became a recluse.”

One of the main talking points of Queen and Country is the fact it’s been billed as Boorman’s last film, not least by the director himself. He puts his decision to retire simply on the toll the filmmaking process takes. “When people ask you ‘Are you making a film?’, they usually mean ‘Are you shooting a film?’, which of course is the shortest part of the whole process. It takes 2-3 years to make a film, and the shoot only takes 6-7 weeks, so what discourages me from going on is the length of time it takes to get the money, casting, designing and all of this.” By ‘this’, he motions to our opulent surroundings. He’s clearly not a fan of the publicity circuit. “I did two weeks of promoting the film in America. I spent ten days in France. It’s that more than anything. I think I have the strength and the intelligence to make a film, but I’m not sure I can withstand everything that surrounds it. It drags on the energy.”

With Boorman retiring, that leaves a number of proposed projects hanging in the air, such has Broken Dream, which has been around long enough to have had River Phoenix once slated to star. “I have two or three things I’d like to have made, Broken Dream being one of them. Another one I have, which I’m very devoted to, is called Halfway House, which is a kind of version of the Orpheus legend. The Halfway House is a place where people go when they die, and my invention is that you go there, and you’re given a tape of your life. You have to edit it down to three hours before you can get out!” We’re intrigued, but Boorman is resolute he’s not the one to make it. “Sometimes I think maybe I will try to do it, but there are mornings I wake up and my bones are creaking and I think ‘No, I won’t.’” The walking stick in the 82-year-old’s hand hints at the creaking bones, but he’s perfectly able to chat and reminisce with perfect recall.

As much as we like the idea of Halfway House, it’d be a hard sell. That said, Boorman has found no ease in trying to fund his films over the years. “It’s actually gotten more difficult,” he explains. “You notice every weekend there are seven or eight films released, and most of them disappear. I don’t know how people get the money to make them, and there’s all these outlets like Netflix that films filter into. But to make a film and get distribution is very difficult, and I’m glad I’m not starting my career now.” In Boorman’s view, there’s too big a gap between the biggest and smallest films. “There used to be a middle ground, which is gone now. You have American mainstream movies, and then a huge gap down to the independent film ghetto, where you can’t really make a film for more than $2-$3 million. If it’s more than that, it’s very difficult, so you have there rather impoverished films being made, with the support of the Irish Film Board or the British Film Institute, and it’s very unsatisfactory.”

Boorman is used to studio work, and acknowledges the pros and cons. “If you work in the mainstream, it’s great in the sense that a studio will supply the money and they will distribute it and advertise it, and spend money on that. On the other hand, you have the studio pressure, in that they send you reams of notes about the script. It’s all about the script. They will try to get you to change the script to what they want it to be before they give you the green light. That pressure didn’t used to be there at all.” He references a famous example. “When I made Deliverance, I never had a single note from the studio. I went off and made the film, came back and showed it to them, and they made no suggestions about changes and that was it. That was very much my experience at that time, in the ‘60s and ‘70s, which was the Golden Age, when studios believed in directors.”

Impending retirement seems to have made Boorman keen to reminisce. The mention of his 1974 oddity Zardoz causes his ears to prick up. “Oh, yeah! I made that after Deliverance was a big hit. I made it for $1 million, negative pickup. That means I delivered the film and then they paid me, so I had to borrow money to make it. It was very ambitious.” He seems bemused but thankful for the film’s cult status “I got a call from Fox to say they were restoring it, and would I contribute to that. I asked why, and they said there was a lot of interest in it.” Boorman can’t help but laugh. “Every time in America, whenever Zardoz gets mentioned, there’ll be a cheer. This film went from being a failure to a classic without ever being a success!”

One of the director’s films that never enjoyed success with audiences or critics was Exorcist II: The Heretic, but even that seems to be getting a second wind. “It’s coming out on Blu-Ray shortly, and we’ve restored the colours, which I was very, very happy about. Geoffrey Unsworth was the cameraman, and he had a special technique to produce these kinds of pastel colours that we were trying to achieve. [On the Blu-Ray] we managed to get the back to how they were at their best.” Even in a work as lampooned as Exorcist II, there’s beauty to be found.

There’s a sincerity to Boorman as a filmmaker, but his works often contain a rich satirical streak. It’s clear in later works, like his 2001 adaptation of John Le Carré’s thriller The Tailor of Panama, but the director traces it back to his early career, and his Fellini-inflected 1970 film Leo The Last. “In a sense, this theme you have in Leo The Last, which is the gap between rich and poor, when Leo discovers his money is coming from slum rents, is in a sense the same theme in Zardoz. The starting idea was the rich getting richer and the poor getting poorer. The rich were living longer as they had better medicine. I thought that if you extend that into the future, you could certainly get to a point where you’d achieve a kind of immortality through science. So, that’s been a theme disguised in many of my films.” Is he suggesting Zardoz could be a sequel to Leo The Last? “Yes.” He doesn’t elucidate on that point, but the suggestion is enough to leave us amazed.

Boorman’s always had his pick of the stars. Even his stranger efforts will have a role for the likes of Sean Connery and Richard Burton. However, as evidenced by Hope and Glory, he doesn’t cast stars for the sake of it. “The financiers always want you to get stars; that’s the perennial thing.” So, how does you get the stars you want? Boorman’s answer is to aim high. “When I made Deliverance, they had very little confidence in it at Warners, actually. They said, ‘We’ll do it if you can get two stars.’ So I got Jack Nicholson and Marlon Brando. Warners asked how much did they want. I told them, and they said that makes the film too expensive. This is the same conundrum I’ve had all my career, and many other directors too.” Still, Deliverance worked with Burt Reynolds and Jon Voight, so no harm done. “Warners suggested making it with unknowns, and making it very cheap. So, I went in the other direction, and they kept beating me up over the budget. In the end, the only thing I could cut was what I had for a composer and orchestra. I cut them, and just did variations on the theme of ‘Duelling Banjos’, which became the score. It probably turned out to be a better score than had it been composed with an orchestra!”

That happy accident leads us to the topic of film scores. His Exorcist II collaborator Ennio Morricone recently bemoaned the state of modern film music, but how does a director approach what he needs musically? “I never think about the music until after I cut the thing together. The only exception was Excalibur. I went to see the Ring Cycle by Wagner, and that was a huge influence on the film, and I felt from the very beginning that Excalibur needed Wagner. I had a score for it, but Gotterdammerung and Tristan and Isolde were key. Wagner said ‘I don’t make operas; I make musical dramas.’ I think that he’d be scoring movies if he lived in our age.”

Stephen McKeon’s IFTA-winning score for Queen and Country is a handsome accompaniment to Boorman’s images, though you can never be sure what will work. “I’ve always had an ambivalent feeling towards music, but there are some instances in the cinema where scores have made a film. Morricone’s an example. His music is absolutely crucial to the Spaghetti Westerns. They’re an identity for the film; they connect to them. I suppose I got that with ‘Duelling Banjos’. It’s so much entered the language, in a way.”

The success of Deliverance, and its assimilation into popular culture has not escaped its creator. “Just the other day someone sent me a t-shirt with two Peanuts characters on it paddling a canoe, and one says to the other, ‘Paddle faster! I hear banjos!”’ Now, that’s completely obscure unless you know the film.” Of course, most people know it. “It’s a curious thing. If a film connects to the zeitgeist and locks in with an audience. It doesn’t happen very often, but when it does that movie becomes part of the culture.” What greater accolade could a director hope for?

Queen and Country is in cinemas now. Read Scannain‘s verdict here.