There’s a fair amount of Her spoilers ahead, so if you haven’t seen the film I’d avoid reading on. Also, go see the film – it’s a stunner!

Summer Finn from (500) Days of Summer. Sam from Garden State. Belle from Beauty and the Beast. These are just a few examples of The ‘Manic Pixie Dream Girl’: a common trope in modern cinema, coined several years ago as “that bubbly, shallow cinematic creature that exists solely in the fevered imaginations of sensitive writer–directors to teach broodingly soulful young men to embrace life and its infinite mysteries and adventures”. Or, if you’re me, a really, really annoying female character that spends their time self-consciously doing things like blowing bubbles, wearing dresses and gazing at the moody protagonist from under long eyelashes. The MPDG is everywhere: kid’s movies, rom-coms, comedies, romantic dramas…sometimes it feels as though there is no escape from the MPDG in cinema. However, all is not lost: the backlash has come. One is reminded of 2012’s Ruby Sparks, a film which acknowledges and gleefully trashes the idea of this girl. This year’s Her, directed by Spike Jonze, is an infinitely more nuanced meditation on the trope. Let me get this straight: ‘Her’ is not a straightforward love story. It does, however, feature a sensitive, brooding protagonist, stuck in a rut until he meets the love of his life. The comparison seems obvious: until we look at the character of Samantha herself.

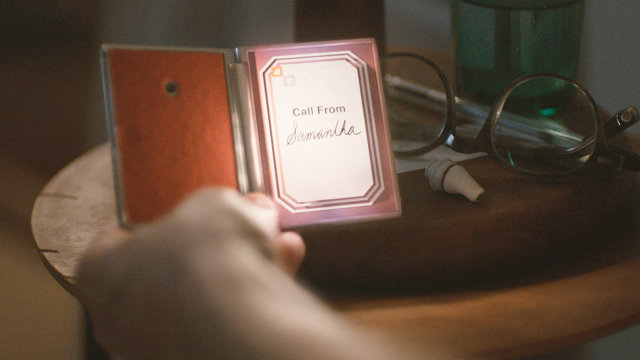

In Her, the idea of the “perfect girl” is taken to whole new heights: Samantha responds to Theodore (Phoenix), intertwining her budding personality with his. It seems that an OS is a consciousness that adapts to whoever it’s owned by – Manic Pixie wet dream of a girl who becomes exactly what the protagonist wants her to be. As Samantha becomes more and more ‘human’, she becomes more giggly, loving and , as Theodore repeatedly tells us “excited about the world” . Had she a body, it’s easy to imagine her giggling, twirling and wearing perfect winged eyeliner a la Zooey Deschanel. She’s literally everything a sensitive, lonely man could want: sex and adventure without the need for anything truly grounded in reality.

But little by little, the audience realises what Theodore hasn’t: Samantha does not exist. That’s not to say she isn’t ‘real’ – but she can’t ever exist properly. This aspect of the character prevents her from becoming the fully-fledged Manic Pixie – yes, Samantha teaches Theodore to open up, to move forward and to love. It’s touching that she does all this without ever being “human”. And what’s quirkier than not having a body?! But ‘Her’ fails to fulfil the MPDG promise spectacularly – in that Samantha eventually transcends Theodore, and Earth. In the second half of the film, Samantha learns to let go of her desire for a body, growing more intelligent and further from Theodore with every passing moment. Samantha develops her own consciousness and will, free from Theodore, something that the classic MPDG’s of cinema fail to do. The film climaxes when all the Operating Systems leave Earth forever – to a higher plane of being. Samantha is so clever, so original, so her own self, that she leaves the entire race that created her. Independent of her moody protagonist, Samantha leaves for her own whole new adventure. It’s almost as though she used Theodore to grow and develop, and helping him was a handy by-product.

Her is not strictly a film about gender roles; this is merely one interpretation of a beautiful film. It explores human nature, our relationships with technology and, of course, loneliness. Samantha’s journey to becoming her ‘own’ is one of the elements of the story that struck a cord with me, however. Having been constructed as an entity designed to do humankind’s bidding, the OS’s eventual desertion of Earth makes the audience wonder about not only our iPhones, but ourselves, too.

[yframe url=’http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ne6p6MfLBxc’]