It is one of cinema’s many ironies that the makers of the images that fill our eyes live in the shadows of their own lighting, and their names remain mostly anonymous. This is why among all of the brands buoying up Cannes, some should also be of the industry and host events that spotlight these heroes of the crafts of cinema. This year, the eye that immortalised the vivacity of Madonna in Desperately Seeking Susan, whose lighting and angles ensured that we felt the intimate longing between Cate Blanchet and Rooney Mara in Carol was celebrated.

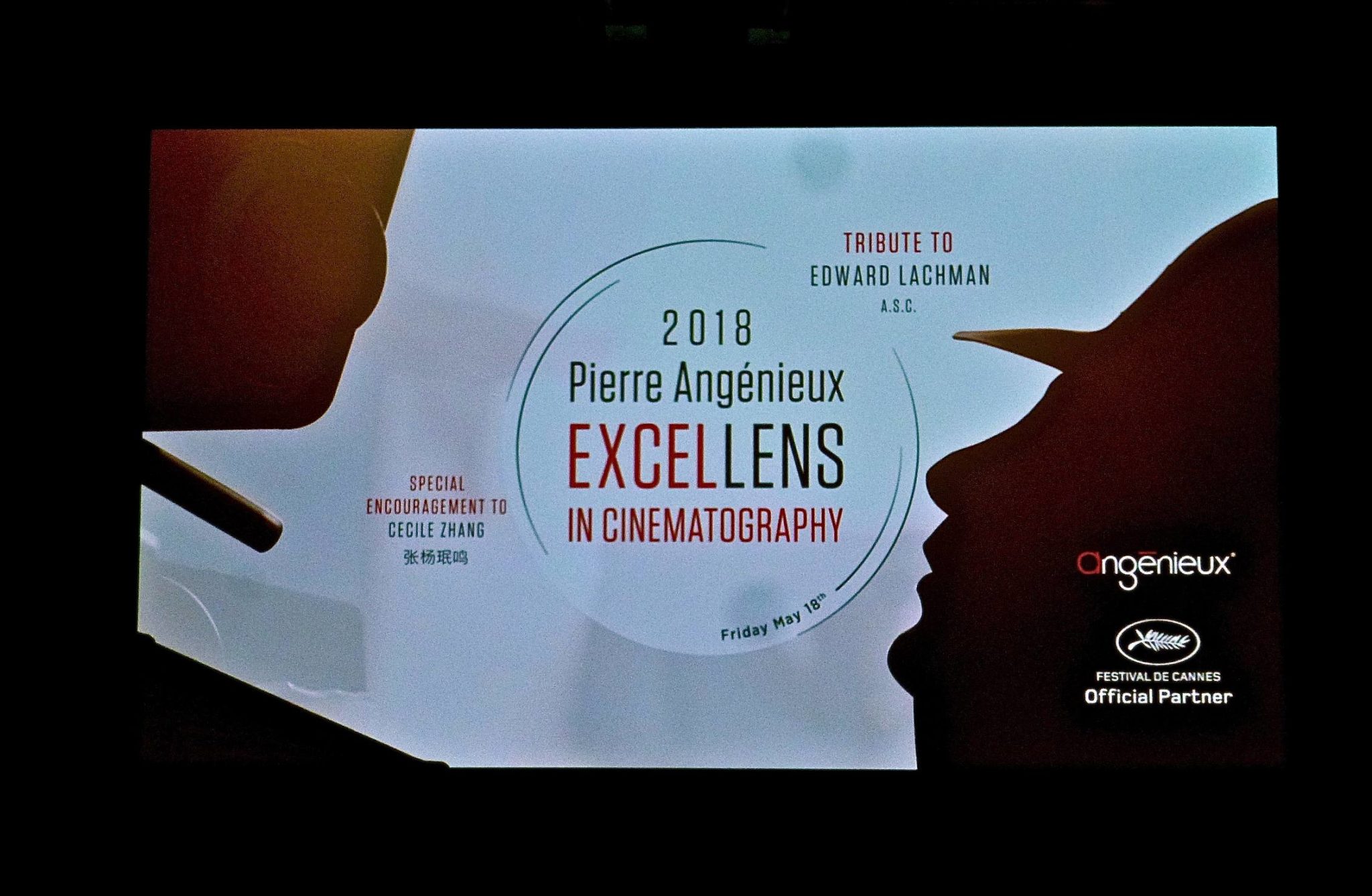

In Cannes 2018, the sixth “Pierre Angénieux ExcelLens in Cinematography” tribute was accorded to Ed Lachman for a career spanning 45 years and comprising an eclectic mix of over 75 films and documentaries, Edward Lachman has served as director of photography on films by Werner Herzog, Jonathan Demme, Susan Seidelman, Dennis Hopper, Paul Schrader, Mira Nair, Andrew Niccol, Robert Altman, Todd Solondz or Larry Clark with whom he co-directed the very sensuous Ken Park.

Pierre Angenieux (1907-98) was a French optician who went on to found the prestigious lens manufacture in 1935, improving optical research techniques and inventing the zoom lens along the way. Since the honour’s inception in 2013, tribute has been paid to Philippe Rousselot, Vilmos Zsigmond, Roger A. Deakins, Peter Suschitzky and Christopher Doyle. This year’s innovation saw Angénieux adding a newcomer category to sit beside the recognised masters of the craft. Thus Cecile Zhang – who graduated with honors from the Beijing Film Academy – was also honoured on the basis of her reputation and inventive the creative qualities of her work to date.

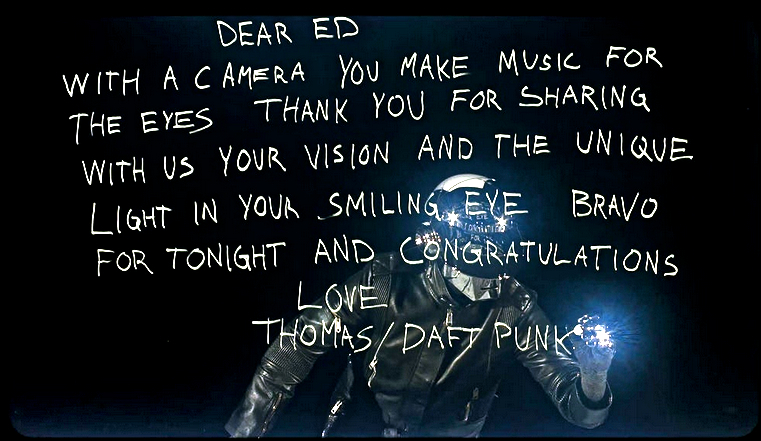

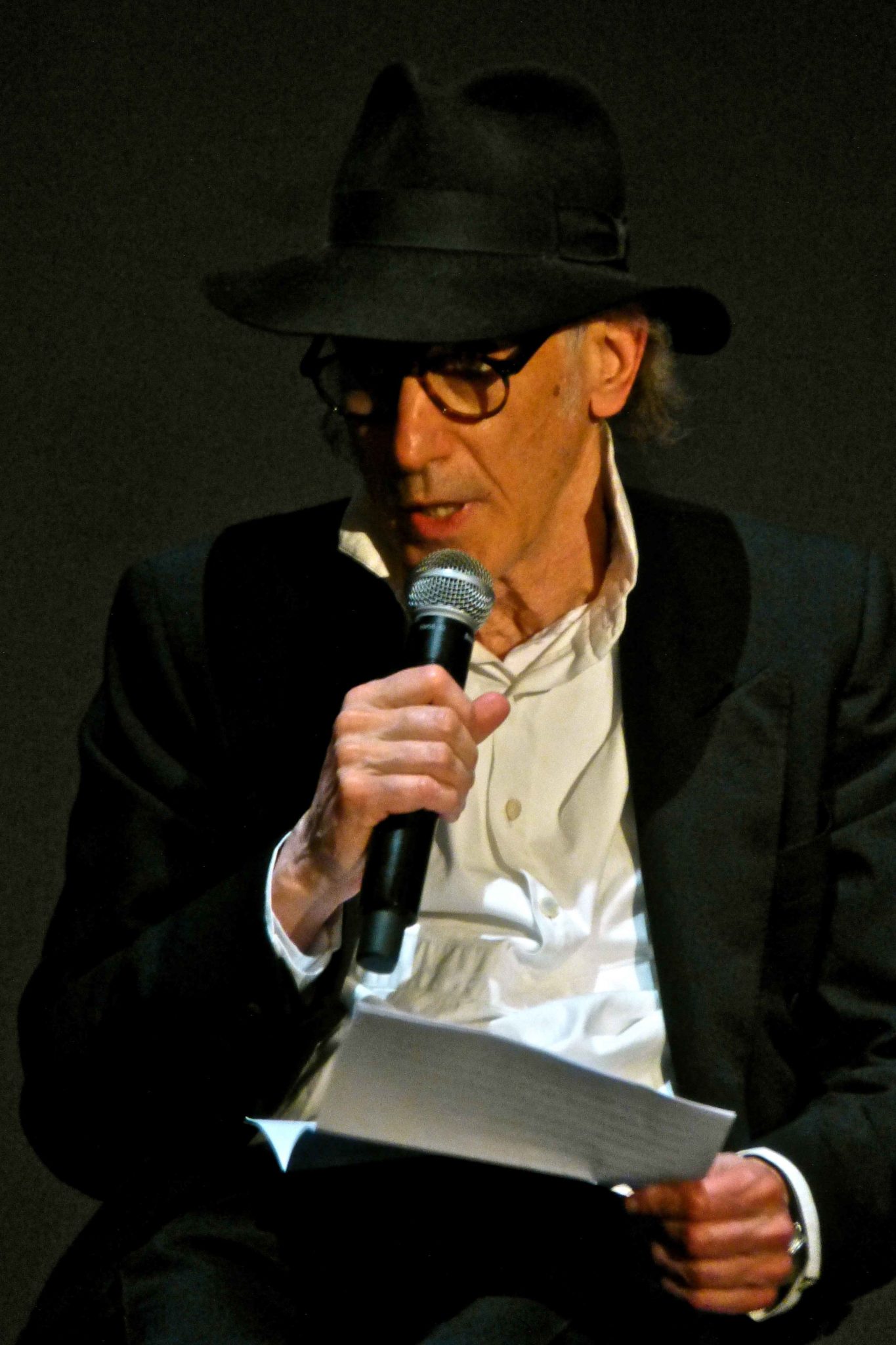

As interesting as many a Cannes film, the 2-hour ceremony of speeches, film extracts and testimonials, live and by video, including a warm and inventive video from Thomas of Daft Punk, with whom Lachman has collaborated. Most recently Ed Lachman’s name has been closely associated with Todd Haynes, who gave a very personal description of his admiration, gratitude and friendship. In his own words:

“Sometimes you get lucky—in life, in love, in filmmaking—and find the ones who reveal to you, like it or not, yourself.

Your obsessions, your language, your frame.

And that’s Ed Lachman.

For many of us it was Susan Seidelman’s Desperately Seeking Susan that first stained our awareness, literally, with its unholy glaze of burnished reds and phosphorescent greens. A similar sense of beautiful contamination would invade the films that followed and reveal, like in the slow nocturnal creep of backseat shadows across the face of Willem Dafoe in Light Sleeper, that gorgeous mix of the alien and the true.

Someday, I remember vowing to myself, I want to work with this guy.

Looking back, all the things I thought we’d invented together—that infernal glow, the mesh of warm and cool, the soiled palette—were things Ed was onto from the very start. But in finding him, and assigning to his unyielding eye, a series of cinematic excavations, I found a partner who shared my interest in every detail. Someone who doesn’t stop looking, or pushing to make it better, whatever it takes.

Eddie was born in New Jersey, the son and grandson of movie theater exhibitors and amateur camera buffs. But it took a detour through art history and Italian neorealism to kindle his love for the power of film. It doesn’t hurt when one of your earliest mentors, Bernardo Bertolucci, invites you to the premiere of The Conformist at the NY Film Festival in 1970. Or when you begin your tutelage, a few years later, operating for Sven Nykvist, Robbie Muller and Vittorio Storaro. Ed’s roster of filmmakers is a compendium of late 20th century auteurs, from Godard, The Maysles, Herzog and Altman to Soderbergh, Wenders, Schrader and Seidl. He even made a short in Germany with the Fassbinder clan where Rainer performed the off-screen voice of Marlene Dietrich. But in recent years, I am proud to say, there is no director he has been more closely associated with than me.

The films we’ve made together—Far From Heaven, I’m Not There, Mildred Pierce, Carol, Wonderstruck—embody a kind of phantom history of the 20th century, where cinematic memory reframes stories about women in houses, or children in cities, private lives and public lives, black lives, secret lives. They are films that are never unaware of the languages they cast to tell their stories. So this is where it all begins, in the language of color and shadow and grain, movement or stasis. As Sirk once said, a director’s philosophy is lighting and camera angles. That through the movement of the camera we are moved.

Whether in black and white or color, in 16mm or 35, we’ve continued shooting on film, less out of some material orthodoxy than a kind of search for the missing body of our medium. And maybe that’s the point, that the body is always missing, and that’s we why hunger for it. For Ed is no purist. He engages new technology. His life and work reflect an enthusiastic devotion to both tradition and experimentation, to his greatest predecessors and the fraternity of his peers. This insatiable appetite to be inspired, this contagious enthusiasm and curiosity, he brings to everything he does.

His brilliant team have redefined loyalty—from the genius of gaffer, John DeBlau, to the unflappable grip, Jimmy McMilllan and soulful operator, Craig Haagensen. These are the partners with whom Ed brings it all to life, under every conceivable financial or physical challenge. But make no mistake. Ed Lachman will outpace us all. Which is one more reason why I love and revere this incredible man, his indomitability, his unquenchable spirit, and the partnership we’ve distinguished within this radically gorgeous body of work. Simply put: Ed is an artist. And the persistence of his vision and lifetime of images has forever changed the way we see the world.”