He rises in the window. ‘You’re him, aren’t you.’

Cloaked in black and studded with diamonds. His eyes like nothing you’ve ever seen. He offers a wish, a glowing sphere. You refuse, and it becomes a red and black snake in his hand.

I wake up at nine on Monday and check my phone – what an ugly habit. Thumb open Twitter. The first thing the internet says to me is this: David Bowie is dead. The world changes colour.

Celebrity death is a strange thing. It feels invasive and inappropriate to publicly mourn someone you’ve never met. A man who has left a wife, family, friends – somebody who had been ill for eighteen months prior to his departure. He is lionised and he is critiqued, he is honoured and scrutinized and here I am, trying to figure out why I still have his glitter all over me.

He was a stranger, but because he was an artist he was a stranger holding a lantern. A bright, strange lantern. The lantern is a slice of a faraway planet. The lantern is a crystal ball.

As I flicked through a timeline punctuated with shock and loss, it took me a moment to remember Labyrinth. As though to make all this manageable, I sank into all that sinister glamour, all that innocence and courage. Like many millennial women, Labyrinth was my first real emotional exposure to Bowie. Charlotte Richardson Andrews notes in the Guardian, ‘I was infatuated with Jareth, the goblin king, for the same reasons his adult, vinyl-collecting fans were: his charisma, his queerness, his voice.’

I am the same. My ordinary name in his beautiful, crooked mouth. I don’t remember what age I was, only looking up at him and being full of new lights, he said Sarah. Turn back Sarah, turn back before it’s too late.

I am the same. My ordinary name in his beautiful, crooked mouth. I don’t remember what age I was, only looking up at him and being full of new lights, he said Sarah. Turn back Sarah, turn back before it’s too late.

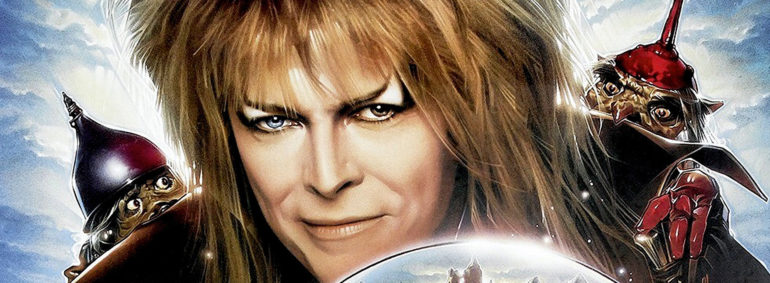

Labyrinth (in case you haven’t seen it) is a gorgeous, lush, dark hybrid work from Jim Henson, scored by and starring David Bowie. There’s even a George Lucas thumbprint. It’s ostensibly a kid’s movie – puppets and dancing and adventure (girl’s baby brother is stolen by the goblin king and she has to navigate a magical maze-realm to retrieve him) but Bowie’s presence as Jareth, said king, shifts the tone darker. His interpretation of Jareth queers the very nature of the fairytale at hand.

In the long list of Bowie’s performed characters, Jareth is profoundly femme, all eyeshadow and iced lips and earrings and feathery hair. But he is also masculine; in the colour of his voice, in the hard lines of him, in his sinister preying on Jennifer Connolly’s blindingly naïve Sarah. Over at Bustle, Casey Ciprani points out, ‘Jareth’s androgyny resembled the gender fluidity that Bowie was embracing himself.’ How could one body, one thin voice could express so much? My eyes were full of him, and feel full of him still: a puzzle I couldn’t work out. A prism, refracting gender.

Bowie here is the fulcrum of this coming of age story. There’s a blur over the binaries of good and evil: relatively little in the way of traditional morality at hand. Jareth is a brat. He’s a monster, capricious and controlling and obsessed – but Sarah is a brat too. She’s indignant and spoilt and resentful. Hoggle’s, Sarah’s goblin guide through the maze, a creep – the first time we see him he is literally pissing into a lake. The detailed, grim puppets are terrifying. Brian Fraud, the designer, is well renowned for his grotesque depictions of magical creatures and here they creep about in three dimensions, full of texture, beady eyed and malevolent. Everything in this world is wrong and dark, but I saw it when I was small enough for something about it to stick. It felt like a fairytale and a music video, powdered then wrapped in gauze. Like Snow White and the Seven Dwarves dancing with The Rocky Horror Picture Show.

Labyrinth, like any satisfying fairy tale is about coming of age and therefore equally about sex. Sarah’s innocence is what is at stake, and Jareth is around every corner, trying to pry it from her. He is at once an evil queen and a handsome prince, and there’s something profoundly attractive about that intersection. Angela Carter succinctly remarks in the Infernal Desire Machines of Doctor Hoffman, ‘Evil is usually attractive, because evil is defiant.’ Jareth defies masculinity and tradition. He’s Doctor Frank-N-Furter dressed as Prince Charming. He has four costume changes, most of which feature deeply lowcut silken blouses, heeled knee-high boots, and black leather gloves.

Objectively, that’s kind of hilarious. It’s awkward, silly, over the top (I chain-watch Youtube videos from the film, cringing softly and affectionately at Bowie’s pantomime of evil). I can’t find it sexy now – I’m not sure I had the wits about me to find it sexy then – but somewhere in between, something about it crystallised, imprinting on me. Isn’t the best attraction kind of silly? Intense, sure, but you could burst out laughing at any moment.

All this in admitting my crush, The Jareth/Sarah relationship in the film can cue many different feminist critiques and conversations: Sarah’s agency is clear at every turn – what she wants to happen, happens. She says take away my baby brother – it’s done. She says let me go, I don’t want you or this – done. Her agency makes spells and breaks spells, she is the rescuer, not the rescued. This forges Labyrinth as a feminist antidote to the musical fairytales we are spun where girls bite the apple and lie down amongst the dwarves until a wealthy bae in a pair of tights gallops up on his stallion to smooch us back to life. Sarah is, instead, the babe with the power.

She embodies many of the trappings of the traditional damsel, or even the animated princess we know so well – she even has a wicked stepmother. She broods over memories of her departed mother, she clings to childish trappings of her youth in stuffed toys and costumes. But rather than frolicking with the talking animals of the labyrinth and singing them songs, she interrogates them for directions. Rather than becoming a live in maid for seven dwarves, she barters with the goblins for safe passage – maybe even manipulates them a little. Sure, she bites the poisoned peach, but in her bleary ballroom moon-eyed dream, she actually throws a chair and releases herself rather than throwing the lips on David Bowie. Sarah waits for nobody.

She embodies many of the trappings of the traditional damsel, or even the animated princess we know so well – she even has a wicked stepmother. She broods over memories of her departed mother, she clings to childish trappings of her youth in stuffed toys and costumes. But rather than frolicking with the talking animals of the labyrinth and singing them songs, she interrogates them for directions. Rather than becoming a live in maid for seven dwarves, she barters with the goblins for safe passage – maybe even manipulates them a little. Sure, she bites the poisoned peach, but in her bleary ballroom moon-eyed dream, she actually throws a chair and releases herself rather than throwing the lips on David Bowie. Sarah waits for nobody.

Jareth’s arc is something different. He loses power to Sarah the further she progresses through the labyrinth. She becomes more lost and in parallel, he loses himself to desire for her. He becomes more impulsive in his punishments of her; elaborate traps and oubliettes, resorting to poison to control her when she won’t allow herself to be emotionally exploited or tempted by his charms. Sarah is an intrepid adventurer disguised as a doe eyed ingénue while Jareth is lovestruck and desperate, despite the illusion of his control. He can’t even claim her when she’s drugged: he stalks her through a dreamy masquerade, a tease, hide and seek. He moves a fan away from his face, coquetteish a moment, then smiles at Sarah lost in the crowd. Cat and mouse, peekaboo. He is blouse has a high neck this time, at least. A ruff. Gemstones.

Sarah Waldron, journalist and my editor over at The Coven, during a conversation about Bowie’s death and the importance of Labyrinth, commented, ‘What disturbed me when I was younger was that Bowie’s character represented the fact that sexuality could be dark – and destructive. That the pull and the push of it could be the same thing. For many women, it was a portent of things to come.’

She’s right. For Sarah, as for the rest of us, there is no happily ever after. There is just a fetch-quest completed, just a step forward and an owl at the window, still watching, still waiting to be invited in. Their dialogue is always combative, often flirtatious. ‘It’s not fair.’ Sarah protests.

Jareth narrows his eyes at her, ‘You say that so often. I wonder what your basis for comparison is.’

Later, more eager to impress her rather than correct her, Jareth swoops down on Sarah, only to lean against the wall like a boy leaning against a locker in a high school drama, ‘How are you enjoying my labyrinth?’ as though somehow, he is impressing her. ‘There is a striking resemblance between the act of love and the ministrations of a torturer,’ notes Angela Carter – and here again is another binary crossed. What at first appears to be a regal cane or scepter in Jareth’s hands is, in fact, a riding crop. It is in this black leather streak of danger that the awakening comes. This is the queering of the prince, the intersection of punishment and reward, ‘Just fear me, love me, do as I say and I will be your slave.’

Sarah’s defeat of Jareth comes in a shocking incantation, a sentence that should be as well spun into fairytales as much as ‘and they all lived happily ever after’ – she tells him, ‘You have no power over me,’ and is freed on her own terms. She does not just say it to the Goblin King, no – she says it to all the stories that once told her she could not choose her own ending. This is true subversion. I didn’t learn my subversion from Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders from Mars, I learned it in a Labyrinth. I learned it from Sarah, and I learned it from Jareth, too.

So repeat the incantation. Repeat it at the end of every fairy-tale that tells you you should sleep for a thousand years, that commands you to slavery, that tells you to cut your hair, that puts your voice in a locket, that puts glass beneath every step you take.

Repeat it at every story that tells you to stay quiet, stay small, stay good, stay on planet earth. Repeat it and draw a bolt of lighting from your forehead to your jaw. You have no power over me.

Edited & titled by Sarah Waldron, with development thanks to Maggie Tokuda-Hall.

[infobox style=’regular’ static=’1′] Sarah Maria Griffin is a writer from Dublin. She doesn’t live in San Francisco anymore. Her collection of essays, Not Lost, was released by New Island Press in 2013, and her first novel, Spare & Found Parts, is forthcoming with Greenwillow Press (Harper Collins) in Autumn 2016. She still can’t believe she gets to hear David Bowie say her name whenever she wants to. She tweets @griffski.[/infobox]

Sarah Maria Griffin is a writer from Dublin. She doesn’t live in San Francisco anymore. Her collection of essays, Not Lost, was released by New Island Press in 2013, and her first novel, Spare & Found Parts, is forthcoming with Greenwillow Press (Harper Collins) in Autumn 2016. She still can’t believe she gets to hear David Bowie say her name whenever she wants to. She tweets @griffski.[/infobox]