When a director gets above a certain age and starts playing around with camera angles, lighting and framing, they’re either crying for attention or they’ve got nothing to lose. With EO, Jerzy Skolimowski is very much in the latter camp. The filmmaking dictum is never to work with children or animals, but if Skolimoski can successfully wrangle the likes of Alan Bates and Vincent Gallo, surely he can cope with any old ass, right?

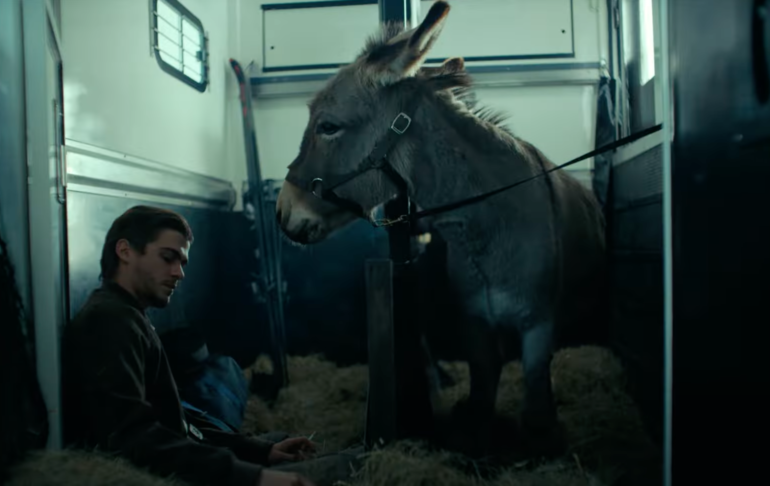

Why are we so often more ready to empathize with animals than people? As Skolimowski demonstrates, the answer lies in the eyes. Many a sequence comes to a close on a close-up on the mild dark eyes of our asinine lead. Poor EO is a donkey trained to perform at a circus. The opening scene sees EO and his troupe having to perform in flashing red lights amidst jarring rapid cuts; think the climax to Guadagnino’s Suspiria, but with no bloodshed and only marginally more ass. We are put in EO’s point of view, before being ripped back into the human world. For starters, the circus is ordered to close as regulations on animal welfare tighten, and thus begins a bizarre odyssey for our four-hoofed protagonist. In other hands, this tale would likely have seen a circushand take the donkey in as both are consigned to the scrapheap, but Skolimowski and co-screenwriter Ewa Piaskowska clearly believe in the strength of their filmmaking ability and the emotions inherent in EO’s odyssey. Moved to an impoverished donkey sanctuary, and after his trainer Kasandra (Sandra Drzymalska) pays him one last drunken visit, EO brays from the depths of a soul that clearly is there, his howls of desperation echo over the Polish valleys and the cinema. EO is one of the most compelling characters in any film to be released this year. Skolimowski achieves this through ambitious but elegant camera angles. By turns, we are in EO’s head, watching him make his way through his strange human world, or eavesdropping on the human dramas that decide his fate from one scene to another. Skolimowski keeps us on our toes, never committing fully to a given register. This could have gone into full whimsy, or embraced a Dardennes-esque realism, but then EO and his ilk aren’t so stoic as to commit to such rigid limitations.

The freedom from any realist trappings helps Skolimowski not only avoid easy comparison to EO’s obvious antecedent, Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthasar. It also allows him to give EO an active role in his story. Those nightmarish red lights and filters interject intermittently whenever a scenario gets too real, and there’s a specificity to the sound design that both envelops EO, and distances him from the surrounding world. The chants of a football team that adopts EO as a makeshift mascot are deafening, as are the punches when hooligans from a rival team assault the fans and EO with equal ferocity. For all its directorial verve, EO is not a happy-go-lucky tale. The poor animal’s well-being is constantly on the line, and dependent on the good (or ill) will of the surrounding humans. At various points, he’s sold for meat, abandoned in a forest and transported across borders. We’re with EO all the way, even if some creative decisions baffle. The score by Pawel Mykietyn leans too much into the whimsy, becoming obtrusive on occasion. One should never complain when Isabelle Huppert is in a movie, but her appearance as an Italian countess (!) takes you out of the film momentarily. Still, these prove relatively minor speed bumps in EO’s journey. By the time we get to the end, and Skolimowski makes his ultimate point, you’ll be amazed how invested you were in this humble creature.