There is no sincerer love than the love of food.” Heaven knows what prompted George Bernard Shaw to say such a thing but there is no denying his remark has stuck with good reason. Religion, all forms of celebration, at least 3 key points in the day, and every high and low of emotion can usually be tied to the cooking, consumption and appreciation (or otherwise) of food. Food is tied to emotion, even the visuals of food will prompt a reaction which of course has been evoked in many a movie.

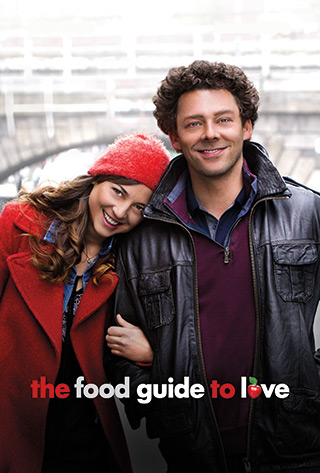

The Food Guide to Love pitches itself firmly in the food-porn camp. It’s clear from the title, and Richard Coyle as a high-profile Dublin food critic and blogger is salivating about his first experience of tapas from the opening scene. The problem though is that from this very first scene you’re left feeling queasy rather than hungry. Coyle’s character, Oliver, is pitched as a happily smug git, his name and reputation entwined with fine dining and fine women. He is lined up for a number of lessons come the end of the movie but there is never an ounce of sympathy for him as he saunters witlessly through the movie. Coyle was charming throughout Grabbers, the 2012 Irish take on a genre staple (horror) but here, as a leading man in a romantic comedy with an Irish postmark, he is an uncomfortable watch. You can almost see him struggle to recall his lines and then feel he must gesticulate wildly to add humour.

The attempts at comedy in the early scenes are all played out to an inexplicably goofy soundtrack. The movie somehow comes across as a cheesy soap, all but missing a laugh track (that said there is a laugh track used at one point and it’s awful). Any comedy tone is muddied with confused flashback scenes which try to explain Oliver’s love for food but instead portray a deeply unhealthy family background. There is inevitably a girl, played by Leonor Watling, who is thankfully a natural talent in the midst of so much over-acting. Why this new relationship works, why it hits a crisis, or how anyone believed that the dialogue, instincts and behaviour of these people is anyway engaging or realistic is all unclear and frustrating. The movie becomes embarrassing with cliché heaped upon cliché as the movie tumbles through a middle act where it has clearly run out of ideas. Events spiral as distance grows between the central pair and are at their most ludicrous in a cringe-worthy scene set outside a fictional Dublin city zoo where a bereaved man with coddle stains on his jumper dances around like a monkey. It seems to never end.

It feels heartless to criticize good effort. It feels heartless to criticize Irish film making. No one sets out to make a bad movie but here it appears as if the makers can only borrow romantic comedy staples and invoke them in such a pallid way that the movie collapses into a mess. The key romance of the film never actually functions for more than a few minutes of running time. The ending gives no mercy, no one has learned anything, the dysfunction if anything has grown, and it somehow ruins the allure of chocolate truffles.